- Home

- John Yunker

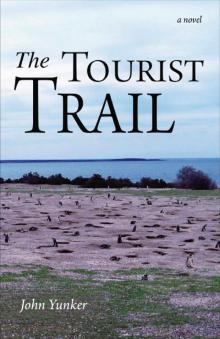

The Tourist Trail

The Tourist Trail Read online

The Tourist Trail

A Novel by John Yunker

Published by

Ashland Creek Press

www.ashlandcreekpress.com

To Midge

Part I: Bycatch

When the land has nothing left for men who

ravage everything, they scour the sea.

— Tacitus

Angela

In darkness, Angela ascended the winding gravel road. She carried a flashlight, but she kept it off. She knew the path well.

The Clouds of Magellan illuminated the white bellies of penguins crossing up ahead. Most stood at the side of the road and watched her pass, their heads waving from side to side. When one brayed, the high-pitched hee-hawing of a donkey, the others responded in kind, forming a gantlet of noise. It was mating season at Punta Verde, and the males were rowdy.

At the crest of the hill, the road veered right and continued for half a mile to the vast empty parking lot where tourist buses and taxicabs disbursed their cargo during the day. Angela continued straight, onto soft dirt and dry patches of grass, sidestepping the prickly quilambay bushes and the cavelike penguin burrows. She stopped at the top of the hill and scanned the wide, arching horizon of the South Atlantic Ocean. A gust of wind nudged her from behind and she leaned back into it, her eyes tracking slowly from left to right. The moon, about to rise, gave the sky an expectant glow. She looked for the telltale lights of passing ships but saw nothing but the stars.

He should be back by now.

The last she heard from him was a week ago. He was off the coast of Brazil and headed south, only eighty miles north of here. She had reviewed the weather charts, but there were no Atlantic surges, no last-second squalls that may have pushed him off course, delaying his return. Perhaps he wanted to stay close to the others. Perhaps he was simply taking his time. Each day, she invented another scenario for why he was not on her shore, carefully ignoring the more rational, more depressing scenarios.

She was only supposed to trek up here once a week, a routine she’d once welcomed, a break from the camp. But since she’d lost contact, she began visiting nightly. Not that she would see him. But perhaps she would see something to explain his absence.

A star crested the horizon. She watched patiently as the light strengthened and inched from right to left, south to north. It was probably a fishing trawler headed for Puerto Madryn, returning from the Southern Ocean, its cavities stuffed with writhing fish and krill and the inevitable, under-reported bycatch. She felt her stomach tighten.

The moon began to bleed out over the water, erasing the ship from view. Angela sat down in the cold dirt and waited. A penguin brushed past her sleeve on his way to an empty nest, where he stood sentry. He, too, was waiting, demonstrating his fealty for a female not yet returned, as well as guarding his home. Every year, the males were the first to arrive at Punta Verde to claim their old nests, under bushes or on the pockmarked hills, in burrows carved into earth. A hundred thousand of them, in a slow-motion land rush, scrambling over this nine-mile stretch of scrubland that hugged the ocean.

The females took their time at sea, gorging themselves on sardines and squid, gathering their strength for the six-month breeding season that awaited them, emerging from the water two weeks, give or take, after the males. Fashionably late. And if they were fortunate, if everything aligned, their mates were waiting at their burrows, their homes clean and dry, new twigs laid out to form a nest.

The males sang when their females returned, and the females sang in response. They flapped their wings and dueled their beaks and circled one another, orbiting, an ancient bonding ritual, an anniversary.

But the penguin standing silently next to Angela would have no reason to sing this year. Of this she was certain. It was simply too late. The females that would arrive had long ago arrived. Chicks were already entering the world, some taking their first unsteady steps. In a few short months, it would be time for everyone to disappear back into the sea.

Perhaps this penguin was in denial, unwilling to accept his loss, or perhaps he was merely stubborn. Angela preferred to imagine the latter. He would stand by that empty nest until the end of the breeding season, and next year he would return and seek out a new mate. An empty nest rarely stayed empty for long. Angela often wondered if penguins mourn the missing, but universities don’t award grants to answer those types of questions.

He should be back by now.

Angela waited another hour, until there were no more lights on the water. She looked one more time at the penguin at his nest, then stood and made her way, flashlight off, back down the hill.

Robert

After the drinks and the dinner service, after the lights were dimmed and the curtains pulled, Robert extracted the television screen from the armrest of his business-class seat. He was not interested in the movies. He switched the channel to the flight tracker—a cartoonish map of the Gulf of Mexico with a little white plane suspended above, pointed south, creeping toward the tip of Colombia. Every few seconds, the screen refreshed itself, updating Robert on the air speed, altitude, distance traveled, time remaining. The dispassionate data comforted him, reminding him that he was making progress, that he was not lost.

He leaned his head back and closed his eyes, hoping to join the symphony of snoring bodies in the darkness around him. But he rarely slept in public. On those rare trips when his body did relent, he would often jerk awake wildly disoriented, spilling drinks and alarming neighbors—a side effect of a life spent constantly on guard. And then there were those rarer occasions when a flight attendant would awaken him to stop his shouting—a side effect of something worse.

Robert opened his eyes, sat up, and took a deep breath. He would not sleep tonight. Instead, he’d spend the next seven hours and forty-three minutes watching a little white plane inch its way to Buenos Aires. He didn’t mind; at least it would be a quiet night, bathed in the blue glow of the flight tracker, his guardian compass, his night light.

The light did not bother the woman passed out in the window seat next to him. If only she could have stayed awake a few hours longer. Dina. A cute but unnaturally tan woman in pink sweats. She was a model from Dallas on her way to Argentina for breast implants.

They’re cheaper there, Dina had told him after the drinks were served. And the surgeons are world class.

She’d flirted with him, drunk on pisco sours. He’d told her he was in sales, a safe cover. Up here, in business class, almost everyone was in sales. Up here, he could have been anyone, which was why he lived for these brief moments of recess, acting out the role of someone else high above the earth, moments when he could imagine life as a civilian, unburdened by the nasty ways of the world, drinking pisco sours with Dina from Dallas.

She’d told him he should be a model, another cover he once used. She ran a hand through his dark hair. He ordered more drinks. He said her before breasts looked perfect as is. She gave him her business card and invited him to Dallas to test drive the after.

For effect, Robert had opened his laptop, pretending to read sales reports. Now he saw that, as if to taunt him, even the computer had fallen asleep. He checked to make sure Dina was still out, then poked the laptop awake. He studied up on the agent he was to meet in Buenos Aires, Lynda Madigan. She would be his partner for the duration of the assignment. Robert didn’t want a partner, let alone an agent he didn’t know, but he needed an interpreter, and she spoke fluent Spanish.

He imagined Lynda looking through a similar file, one on him, and he wondered what else Gordon, his boss, might have told her. Though they were all in the business of keeping other people’s secrets, Robert didn’t want to share any o

f his. But even Gordon didn’t know everything that had happened five years ago. Robert kept those other memories to himself, hoping that he could somehow suffocate them. Instead, he ended up preserving them, perhaps all too well.

Now, as he leaned his head back in his seat, he felt the memories returning. He could see the slowly undulating horizon of ice as he hovered low behind the controls of a helicopter, looking for a Zodiac, a break in the ice, a bright red parka.

As the clouds had descended, so had he, landing on a low, tabular iceberg. He left the engine running and stepped onto the ice. The fog surrounded him, leaving his eyes with little to do but dilate. He started off into the white emptiness, arms out in front, chasing every change in hue, hopeful that he was headed in the right direction, though in reality he was lost in any direction. When the engine noise faded, he called her name, hearing only wind in response.

The ice had begun to shift, growing pliable. He looked down to see the tops of his boots bathed in blue water. The iceberg was descending. He hopped onto a neighboring berg and called her name again, louder. This ice, too, became unsteady, so he hurried to the next iceberg, then the next. The icebergs, once joined together like a completed puzzle, had begun to separate, revealing expanding rivers of indigo, until Robert found himself stranded on a lone sheet of ice, his feet now immersed in the sub-zero water. He could no longer hear the helicopter. He shouted her name, his ankles now underwater, its icy grip working its way up his calves, then his thighs, and he whispered her name, prepared for the end, to be with her again, then his chest, then his arms—

Robert opened his eyes to see Dina leaning over him, her hands gripping his shoulders.

“What?” he asked.

“You were yelling,” she said.

Robert looked at the flight tracker—two hours and thirteen minutes remained until landing, the little white plane hovering over the southern half of Brazil. Dina took her seat again, and Robert reached for a water bottle. He wiped the perspiration from his face. He sat up and noticed the blinking eyes in the darkness around him. He picked up his laptop from the floor and turned to Dina. “I’m sorry.”

“That’s okay,” she said. “Who’s Noa?”

Robert didn’t answer. He had already opened his laptop, pretending to read sales reports.

Angela

Angela watched her assistant extend the goncho, a long piece of rebar that was hooked at the end, into the burrow. Doug was on his knees, face to the ground, squinting into the tiny entrance, nudging the male so he could get a better view of the five-digit number on the stainless steel band wrapped around the penguin’s left flipper.

“Three four six two seven,” Doug shouted over the wind.

Doug was in his mid-twenties and, like most naturalists his age, looked more the part than old-timers like Angela, his senior by a decade. While she stomped around in worn tennis shoes and faded, thrift-shop khakis, he was a walking REI catalog: waterproof boots, camouflage pants with more pockets than objects to fill them, an Indiana Jones hat shoving his messy blond hair down over his ears, a blue bandana around his neck. He was the type of assistant—You say assistant, I say wingman, Doug liked to say—that kept Angela’s program running year after year, fresh from the classroom and eager for an unpaid adventure. Too young still to find the trip down here tedious—the ten-hour flight to Buenos Aires, the two-hour flight to Trelew, the three-hour bus ride on a gravel road to the research station. And it wasn’t much of a research station at that: two cinder-block huts, one shower, and a public restroom they shared with the tourists who stopped to pay their admission fees and to shop for postcards and key chains.

Angela studied Magellanic penguins, named by Ferdinand Magellan in the sixteenth century when the Europeans were busy naming the planet after themselves. At last count, Punta Verde was populated by 200,000 breeding pairs—a count Angela was in the process of updating. The Magellanic species was the largest of the warm-weather penguins, its beak aligned with an adult’s knee, its dominant feature the black upside-down horseshoe mark on its white belly and a circular white stripe that curved up either side of its neck to its eyes. Each penguin had a different pattern of black spots on its belly that tourists often mistook for dirt. This was not the penguin to inspire movies or stuffed animals—it was not as majestic as an emperor, nor as colorful as a macaroni. It lived in the dirt and the muck of wet spring days, snapped at hands that got too close, and often honked incessantly, emitting the sounds of a donkey, earning it the nickname jackass penguin.

“You get that?” Doug asked.

“Three four six two seven,” Angela repeated back without looking up. She leafed through her notebook, her little black-and-white book, as she called it, looking for the five-digit number. She’d banded thousands of birds over her fifteen years at Punta Verde; every penguin fitted with a tag was listed here, with a number, place, and date. Yet despite such a wealth of data, most numbers were entered once and never again revisited. Tagging a penguin was akin to putting a note in a bottle, tossing it out to sea, and waiting for it to return. At night. It wasn’t enough for the penguins to come home; Angela also had to find each one, among thousands and thousands of nests.

“Did you hear that?” Doug asked.

“Hear what?”

“Sounded like an engine. A boat engine.”

Angela looked up and tilted her head back and forth.

“Must be the wind,” she said. She returned to her book.

“Red dot?” Doug asked, hopefully.

Angela didn’t answer right away. While finding a tagged bird was not as statistically significant as winning the lottery, it certainly felt that way at times—and the greatest jackpot of all was when they discovered a red-dot bird.

A red-dot bird was a known-age bird, one that had been tagged the year it was born and hadn’t been seen since. Young penguins typically spent four to seven years at sea before they reached breeding age and returned to their colonies. Yet not all penguins returned, and the reasons had been haunting researchers for years. Because red-dot birds had been tracked since birth, Angela and the other naturalists knew more about them than about any other tagged bird—and they still wished they knew more. But they took what they could get, recorded what they could measure. Whether five years or twenty had passed, finding a red-dot bird always felt like a family reunion.

But she was beginning to hope that this bird was not a red dot. She was reluctant to let Doug handle the bird, even though she knew he was due. It was the natural order of things, for researchers to pass on their knowledge and skills. Once they found a red dot, they had to weigh it, then measure its feet and the density of feathers around its eyes.

Doug hadn’t yet weighed a penguin, and once he did, it would be one less thing he needed to learn from her. One less reason to join her on these trips. One day closer to not needing her at all. Not that he’d ever needed her to begin with. The life of a naturalist was a solitary one, spent more with animals than with people. This was what Angela had wanted, and at thirty-six, she did not harbor any illusions about having children—the birds were children enough—but she did have her illusions about Doug.

Over the past few weeks, Angela had adopted him as she had the birds. Every morning, she was first out of the dining hall to select her assistant and set out for the day’s assignment. Doug was always out there waiting for her, a smile on his tanned face, while the other assistants were still cocooned in their sleeping bags or brushing their teeth in the public restroom. She knew by now not to anthropomorphize the penguins, but she could not help projecting her attraction onto Doug. That he was simply an early riser did not dampen her belief that he had developed a crush on her, that perhaps when he no longer needed her, he would still accompany her. A comforting thought, particularly since they had indeed discovered a red-dot bird.

She looked at Doug and nodded.

“Kick ass!” Doug leapt to his fee

t and unloaded his brown backpack of a caliper, hand-held scale, and nylon strap.

This one had been tagged five years ago. Finally ready to breed, this penguin was probably in his second season at Verde—returning to his natal colony to make a nest, find a mate, and begin a ritual that would last another two decades, if he was fortunate.

During Doug’s first week at Verde, against her better judgment, Angela had let him extract a penguin from its burrow. He had only just figured out how to handle the goncho correctly, and she had been giving him free reign with the birds. He was so passionate that she could not have refused him the opportunity. The scrubby hills were like a playground to him, and she enjoyed looking at the world through his sharp blue eyes, eyes that would wink at her on occasion across the dining room, a wink that took a few years off her life. Sometimes she imagined herself his age again, not yet jaded by the drudgery of Ph.D. politics.

She never doubted her ability to attract men, only her ability to keep them around. Her life was a migratory one—six months here, six months in Boston, the cycle repeating over and over again. While most women her age were now cuddling their newborns, she was crouched over burrows in the relentless southern sun. Her face had begun showing signs of the mileage, wrinkles to the sides of her eyes, ridges that caught the dust like snowdrifts.

She remembered the first time she’d held a penguin in her hands, a fierce little lapdog, all muscle and motion, felt the tightly woven feathers, gripped that firm, fibrous neck as its beak thrashed dangerously about. She remembered the joy of holding this creature that spent most of its life in the water, that only for the sake of raising its young bothered to set foot on land, that this gorgeous awkward creation was now between her two straining hands. She never forgot it. Her teacher was Shelly Sparks, the director of the research camp, who had later recruited her for the job Angela had now: teaching Doug.

The Tourist Trail

The Tourist Trail